I think I’ve told you once or twice before now how obsessive I can be. Well, I’ve always been like that. When I was a kid, I was really obsessed with Shakespeare. Not mildly obsessed, really obsessed: I read his plays and his poetry, I memorized large chunks, I read about him, I went to a Shakespeare camp three summers in a row. I was obsessed. I wish I’d had this book then… but since I didn’t have it then, I’m glad I have it now. And, no, since you ask, I don’t remotely care that it’s too old for the Changeling. She’ll grow into it.

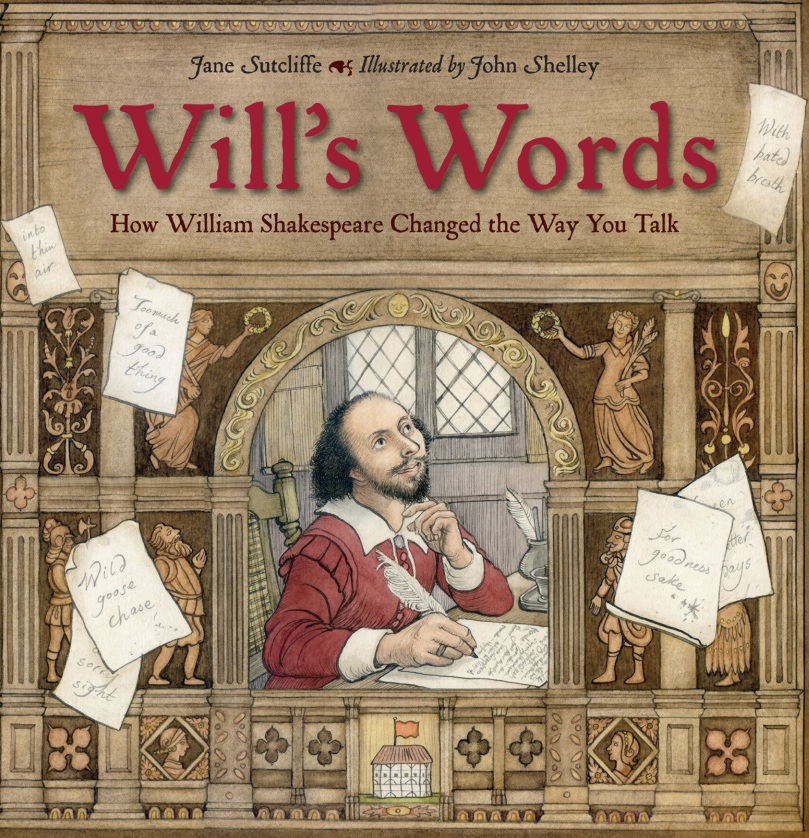

The book is Will’s Words: How William Shakespeare Changed the Way You Talk, by Jane Sutcliffe, illustrated by John Shelley.

That gorgeous title page shows you a good deal of what’s going on in the book itself, as a good cover is wont to do! You see Will writing, you see symbols of the country, theatre, the Globe Theatre in a frame all around him, and you see his words flying on slips of paper out of the window of his century and into ours. Will is in colour, and the frame around him is in the sepia-tinted colours of our distance through time. I love it. When you open the book, though, the sepia distance is gone, vanished. We’re now immersing ourselves in the hustle and bustle of Elizabethan England.

Remember when I talked about I Use the Potty and praised the use of simple lines and a limited palette? This is the polar opposite. John Shelley deserves fame and fortune for the rich and detailed watercolour paintings which form the scenery for this book. If this book is a theatre, then the text is the play, the voice, the soul of the theatre, and the artwork provides the set, the props, the very structure of the stage itself. John Shelley’s exquisite art, carefully researched and beautifully executed, provides the wherewithal to bring the text truly to life.

But what about the text, you might ask. I’m glad you did ask. The text is a mishmash of elements which are united in a love of words. We start with a note from the author explaining that she really wanted to write a book about the Globe Theatre and William Shakespeare, but she found that the language was a nuisance: she kept tripping up and using Will’s words as she wrote. Thus, the nature of her book changed. She still wrote about the history of the theatre in London, still wrote about the Globe, and still wrote about Shakespeare. Now, however, one side of the two-page spread has a little boxed text with some history of the theatre (Did you know that a play would be signaled by raising a banner or flag from the playhouse roof? I remember loving that when I was a kid.), and the other side of the spread has definitions and explanations of expressions which come from Will– thus, Will’s Words (for example: “money’s worth,” which comes from Love’s Labour’s Lost, Act 2, Scene 1).

And so we walk through three stories: the story of the making of the book, the story of the theatre in London, and the story which ties the other two together: the story of language, from Will’s day to our own. This is typical of Charlesbridge publications: they rarely have just one facet out there to grab you. If a Charlesbridge book can’t get you to fall in love in three different ways at once, it’s not a Charlesbridge book!

What’s marvellous about the story of the language is this: unlike the “Shakespeare’s insults” t-shirts, mugs, and other gadgets you’ll see in theatre gift shops, this book isn’t focused on the arcane and the unfamiliar. It’s focused on words you might use any day of the week without realizing they have a connection to Will Shakespeare. Either he invented them, popularized them, or revived them when they were fading into disuse… in danger of being pronounced dead as a doornail (another of Will’s Words).

Now, the child I was didn’t mind the arcane and the unfamiliar in Shakespeare’s language. I’d even say I revelled in it: words like “mooncalf” delighted me. But I bet that my classmates would have truly benefited from a book like this, back in Grade 9. And so could I. To me, it would have been more fodder for my love of language. To some of them, it could have been that one connection they needed to get Shakespeare to make sense. You see, for some of my classmates, I recall, Shakespeare might as well have been Beowulf for all they could see a relationship between his English and their own. To find out that words like “fashionable” became popularized (or… fashionable) because of Shakespeare might have given that point of connection which could have helped them give him a second chance.

But here’s the crux of the matter: between the art and the text here, this book really brings Shakespeare’s England and his theatre to life. You see the bustle both in the streets and backstage; you see that the language isn’t so far-off and sepia-tinted, but right next door to your own. The world starts to jump off the page and into your own eyes and mind and life. I find myself feeling that tingle I used to feel when I opened Hamlet or A Midsummer Night’s Dream as a girl… maybe it’s time to break out the Shakespeare again! In other words, this book is inspiration.

I see one danger: this is a picture book. It’s also a picture book I see as belonging in every high school class with reluctant readers of Shakespeare. I know for a fact that I’d have loved this book when I was a high school student. But because of pesky prejudice, too few people hand picture books to high school readers these days. Well, I object! I think that this belongs not only in the 7-10 range recommended by Charlesbridge (although they’re definitely pitching it right, don’t get me wrong), but older, too.

Let me put it this way: I feel inspired by this book. I look forward to seeing it inspire a whole new generation of readers of Will’s Words, too. Let’s read on!

[…] Will’s Words: What greater transition is there than the transition of the whole English language? This book is about both the fluidity and the staying power of language: it tells us all about how Shakespeare’s world worked, and how his language emanated from his world. At the same time, it emphasizes elements which endured, how phrases like “dead as a doornail,” which originated with Shakespeare, can’t apply to him as long as his contributions to the English language endure. […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] entered my credit card number. It was the beginning of my Charlesbridge obsession (do you remember Will’s Words, too?) and remains a favourite. The thing is, when I bought it, the Changeling was a bit young for […]

LikeLike