Last week I went to the Harvard Book Store to buy a few books. They had just run out of the ones I wanted so they kindly ordered them in for me, but it’s terribly rude to leave a place without buying something so I came away with Finding Winnie: The True Story of the World’s Most Famous Bear, by Lindsay Mattick, illustrated by Sophie Blackall. The sacrifices I make for politeness, folks.

Are there books which consistently make you cry? Well, I’m not a terribly weepy person on a regular basis. I don’t cry over just anything. But when it comes to books, I can be a bit more susceptible, it occurs to me. I mentioned Tess of the D’Urbervilles yesterday? That one tears open my heart and leaves me a sobbing mess. Maybe that’s unsurprising: I’m pretty sure that’s what Hardy was going for as Tess is progressively abandoned and lost to the point that her entire life and being are abandoned and lost. But there’s another type of book which elicits another type of tears: books about the world turning and time going by. Books about love which endures through that time. Oh, Lord-a-mercy. Holy crap. Even typing those words brings prickles to my eyes as I think about Love You Forever by Bob Munsch, or the ending to Outside Over There by Maurice Sendak. And here’s another book in that category.

I can now definitively affirm that this is a weepy book for me as it’s been requested on a daily or multiple-times-a-day basis since I bought it. Let’s see if I can get through telling you a bit about the story without blinking my eyes with a little more than usual vigour. The story begins with a boy requesting a bedtime story, a true story about a bear. His mother tells him about a vet named Harry Colebourn from Winnipeg who has to leave for WWI to care for the horses at the front. (And, yes, I love the Canadian connection.) On the way, he sees a trapper with a bear cub, and being a mensch, he buys the cub and cares for her. He names her Winnipeg (she’s called Winnie) and brings her along to the training camp in England. When it comes time to go to the front, however, he can’t bring his beloved bear into danger, so he brings her to the London Zoo (oh, crap, there go my eyes– that page is beautiful).

Fast-forward to a little boy named Christopher Robin Milne who goes to the zoo and sees a special bear. They make friends, and Christopher Robin is even allowed in to play with the bear. He names his own stuffed bear after her: Winnie-the-Pooh. When Harry Colebourn comes back from the war he’s happy to see his bear loved, and returns to Winnipeg, where he has a family. Several generations later, here we are with Lindsay and her own son, Cole, named for Harry Colebourn, flipping through an album before bed and going over the family story and, yup, I’m sniffling a little.

I think our question is this: what gets my eyes prickling with sweet tears here? There’s a few different strands, of course. One is that we’re talking about a story we all know– Christopher Robin and Winnie-the-Pooh. Finding something a little special behind those books would obviously elicit some emotions. But that’s not all, and I know it. I know that it’s the family aspect: it’s not Milne’s story (nice as that was) which made my voice crack and tremble over the last few pages; it was Harry’s and Cole’s. It was tracing family history, sepia-tinted but still clear, and awash with love through time (love of the bear, love of each other, love of a child), which got me going as I read aloud Lindsay’s words to Cole: “When I saw you, I thought, ‘There’s something special about this Boy.'” (“OK,” say I to myself, blinking furiously, “Don’t we all think that when our baby is born?” “Why yes,” I respond. “That’s the point. That’s why you named your daughter after your own grandmothers. Now hand me a tissue.”)

Harry’s love and sympathy for a poor motherless bear cub is palpable. (“What do trappers do?” asked Cole. “It’s what trappers don’t do. They don’t raise bears.” “Raise them?” “You know,” I said. “Love them.”) Harry raises Winnie. He loves her. The refrain throughout his section of the book is his struggle to make up his mind about what to do with Winnie at each turn of the war: the struggle between his head and his heart. Consistently we read, “But then his heart made up his mind.” Unlike that trapper, God rot his bones, Harry can’t leave Winnie anywhere she won’t be loved, so first he buys her (for twenty dollars, a fortune in those days). Then he takes her to England. Ultimately, he makes the hardest choice: he takes her to one of the world’s best zoos. And that moment of painful love is the first place where the tears start: you think about war, and how the war broke up so many families… and here was another painful decision. Even after the war, he sees that she is loved and cared for, and, seeing that, he lets her stay.

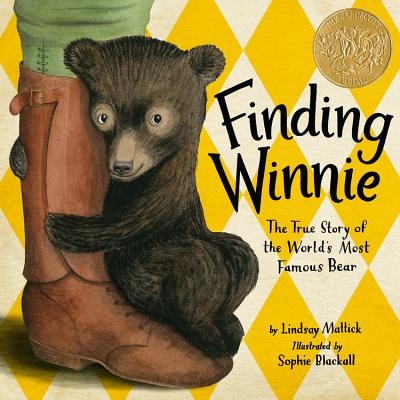

Let’s pause here a moment to think about another aspect of this book which draws out the love at the heart of the story: the illustrations. You’ve probably seen Sophie Blackall’s work around. I think this is some of the finest I’ve seen by her. The cover illustration (scroll up) of that sweet little bear hugging Harry’s boot shows a confidence and affection which instantly elicits a smile. But then you turn the book over (sorry I can’t find a picture of the back cover online, and my camera’s inaccessible right now): There’s another leg, and a little hand dangling down. And from the hand dangles a little bear. Now here’s a puzzle for you: which boy and which bear? Is it Christopher Robin with Winnie-the-Pooh? Or is it Cole with his own beloved Bear? Who is it? Answer: it doesn’t really matter. What matters is that we all know that grip, that dangling hand confidingly wrapped around a soft bear’s paw. Winnie clung to Harry, until she had to go to the zoo. Christopher Robin and Cole clung to their own bears, made their own loved connections. And Sophie Blackall captures those moments beautifully.

I love the Winnie-the-Pooh connection to this story; it wouldn’t have the same cultural resonance without that link into children’s literary history. And yet the interesting thing is that knowing Pooh isn’t necessary to appreciating Winnie. The Changeling is too little to really know Pooh: she hasn’t read The House at Pooh Corner. Her favourite Milne poem is “The King’s Breakfast,” which doesn’t mention Pooh at all. And yet she adores Winnie. She loves watching Harry feed and care for her. She loves the page when Winnie is left at the zoo. There’s something special about that bear, whether as Winnie or as Pooh, and Lindsay Mattick and Sophie Blackall truly draw that Something out.

“It’s OK,” the Changeling assures me as she pats my back. “She found her mummy.” Well, “mummy” aside, my daughter is right: Winnie did find her family, and even her legacy, and it continues.

But I warn you: if you’re prone to weepy sentimentality, make sure you get an extra box of tissues when you buy this book.

[…] Finding Winnie (picture book, a good story to it) […]

LikeLike

[…] Oh, the glorious pictures. Remember, this is the Sophie Blackall of Finding Winnie, and, you know, all of her other work. She doesn’t need me to advertise her, but, please, […]

LikeLike